Over 31,000 fans made their way to the Fens to watch the 62-54 Red Sox take on the 62-56 California Angels for Friday's series opener, the first of a four game set with the Halos. Just one week earlier, California had swept a three game series from Boston, sending the Cardiac Kids back to Beantown on a down note in the wake of an ugly 2-7 road trip. Boston was in the thick of a pennant race, but slipped to fourth place in the standings following a 7-4 loss to the Tigers the day before. Even so, they were still just three and a half games out of first place when Tony C. stepped up with two outs in the bottom of the fourth inning that fateful night.

If not for hurling one of the most infamous beanballs of all time, nobody would remember Hamilton and his 32-40 career record, compiled with six different teams across his eight year major league career. Hamilton had displayed a penchant for wildness since arriving in the Show; as a rookie with the Phillies in 1962 he paced the major leagues in wild pitches (ranked in the top seven three times) and led the NL in walks. For his career he recorded nearly as many walks (348) as strikeouts (357). The irony was that '67 represented a career year for Hamilton, who went 11-6 with a 3.35 ERA. He started the season with the Mets, and if he'd remained there he never would have had the opportunity to throw a single pitch to Conigliaro that season (decades before interleague play was introduced). But, as fate would have it, New York dealt him to California in exhcange for Nick Willhite, an even less effective pitcher who never played another major league game after the season ended. How such a pointless trade even came to fruition is beyond me.

If not for hurling one of the most infamous beanballs of all time, nobody would remember Hamilton and his 32-40 career record, compiled with six different teams across his eight year major league career. Hamilton had displayed a penchant for wildness since arriving in the Show; as a rookie with the Phillies in 1962 he paced the major leagues in wild pitches (ranked in the top seven three times) and led the NL in walks. For his career he recorded nearly as many walks (348) as strikeouts (357). The irony was that '67 represented a career year for Hamilton, who went 11-6 with a 3.35 ERA. He started the season with the Mets, and if he'd remained there he never would have had the opportunity to throw a single pitch to Conigliaro that season (decades before interleague play was introduced). But, as fate would have it, New York dealt him to California in exhcange for Nick Willhite, an even less effective pitcher who never played another major league game after the season ended. How such a pointless trade even came to fruition is beyond me.So while Hamilton was his way to building a forgettable major league career during the '60s, a talented kid named Tony Conigliaro was busy making history.

The homegrown boy born in Revere and attended St. Mary's High School in Lynn signed with the hometown team in 1962, the year Hamilton made his major league debut. He needed all of one year of seasoning down on the farm, where he blasted 70 extra base hits in 83 games, batted .363 and slugged .730. He was ready. The Red Sox, coming off their fifth straight season below .500 and struggling to draw fans following the retirement of Ted Williams, wasted no time in promoting the 19 year-old slugger to the big club. He started on Opening Day, and in his first Fenway Park at-bat he launched a go-ahead home run into the net above the Green Monster off Chicago's Joe Horlen. The Red Sox won, 4-1, helping lift the spirits of the 20,000+ fans including Ted Kennedy, on hand to represent his slain brother during the somber pregame ceremony. A star was born.

Broken toes and a broken arm caused him to miss all of August, derailing his stellar rookie campaign. Had he stayed healthy, he probably would have eclipsed 30, possibly 35 home runs (he finished with 24 in just 111 games, roughly two-thirds of a season) and likely would have given Rookie of the Year Tony Oliva a run for his money. As it were, he still produced a remarkable .290/.354/.530 triple slash line, good for a 137 OPS+. The following season, he became the youngest home run champ of all-time when he lead a weak American League in home runs with 32, the lowest total for a league leader in the Junior Circuit since Larry Doby's 32 eleven years before. He benefitted from a declining Mickey Mantle and injury that limited three-time reigning champ Harmon Killebrew to only 113 games. Needless to say, he avoided the dreaded "sophomore slump" that plagues so many stars and was one of the few bright spots on a hapless Red Sox squad that lost 100 games.

1966 brought little improvement for the Red Sox, who lost 92 games and barely beat out the Yankees to avoid finishing in last place. At least Conigliaro managed to stay healthy, playing in 150 games and piling up 628 plate appearances, both career highs. He also posted personal bests in doubles, triples, and walks. His seven sacrifice flies led the American League. In '67 he was on his way to another stellar season. He made his first All-Star team despite missing 21 of 80 first half games. On July 23rd he slugged the 100th round-tripper of his career with a two-run shot off Cleveland's John O'Donoghue, becoming the youngest player in AL history to reach that benchmark.

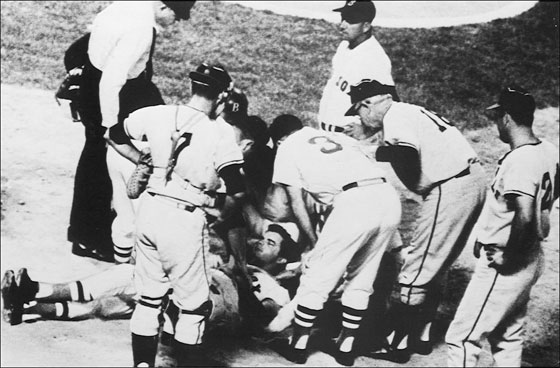

He had a reputation for crowding the plate, for standing over the dish and daring opponents to throw inside. But pitchers rarely made him pay for it; he was beaned just five times per season from '64-'67. When he was slumping, he inched even closer, and on August 18th, 1967 he was in quite a slump; over the previous three weeks he had batted .192/.228/.247 with just one home run. Locked in as the team's cleanup hitter all summer long, he had been dropped him to fifth, and then sixth in the batting order. He hadn't batted that low in more than two months, but fiery skipper Dick Williams desperately needed one of his top hitters to snap out of the funk, and soon. After roping a single to center in his first at-bat, perhaps he had finally emerged from the depths.

But we'll never know. Just as we will never know how many home runs Conigliaro would have swatted had an errant fastball not curtailed his promising career. Many believe he would have approached 500. Through 1967, baseball-reference rated Frank Robinson--a Rookie of the Year, 12 time All-Star, Gold Glove winner, Triple Crown winner, two-time MVP, and first ballot Hall of Famer with nearly 600 career home runs and 3,000 hits--as the most similar player to him. I doubt Conigliaro would have put together that kind of career, especially given his injury woes, but that should give you an idea of the kind of path he was on.

But how many circuit drives would he have amassed? Let's start in '67. Had he stayed healthy, I projected Tony to finish the year with 28 home runs--his average from '64 through '66. Obviously we don't know how he would have performed under the stress of a pennant race, but sabermetrics have proven that such "pressure situations" have little, if any, influence. Besides, for the sake of the projection you have to remove unforeseen variables such as trades and serioust injuries. He ends the season with 112 long balls.

He missed all of '68 recovering from his injury, then whacked 20 home runs to take home Comeback Player of the Year honors in 1969. Accordingly, let's average his projected '67 total with his actual '69 total to give him 24 dingers for 1968. He now has 156 home runs before his 25th birthday. In 1970 he enjoyed the most productive season of his abbreviated career, slamming 36 home runs and piling up 116 RBI. That gives him 192 taters.

A player's prime years span from age 25 through 29, so let's assume he could have sustained that production for another four seasons. Four multiplied by 36 is 144 additional home runs. When he celebrates his 30th birthday before the 1975 season, he's sitting on 336 career blasts. Most players (especially back then) begin to decline during their thirties, so let's have him suffer a 10 percent decline through age 32, followed by a 15 percent decline in his age 33 and 34 seasons, then a 20 percent decline his age 35 seasons gives him 33, 30, 27, 23, 20, and 16 home runs over those six years, an extra 149 four-baggers bringing his career total to 485 through the 1980 season. All he has to do is hang on for one or two more years and he reaches the magical 500 home run mark at a time when the club was much more exclusive; Hank Aaron, Babe Ruth, Willie Mays, Robinson, Killebrew, Mickey Mantle, Jimmie Foxx, Ted Williams, Willie McCovey, Ernie Banks, Eddie Mathews, and Mel Ott. A dozen legends, all of whom made it to Cooperstown.

Conigliaro would have followed them there.

|

| Conigliaro (left) may have passed Ted Williams' total of 521 career home runs and joined him in Cooperstown |

No comments:

Post a Comment